Second Hand Conversations With Irene: Remembering Long Enough

By Lilianne Lugo Herrera (University of Miami, USA) / April 14-18, 2021

Undermain Theatre, directed by Sorany Guiterrez; Producing artistic director: Bruce DuBose

Second Hand Conversations With Irene is inspired by Cuban-American playwright María Irene Fornés (1930-2018), but it is not biographical. Fornés’s legacy is marked not only by her work as playwright and director, but also as a teacher and mentor, especially as founder and director of INTAR’s Hispanic Playwrights in Residence Lab. During the 80’s and 90’s, her most prolific years, Fornés was central to the emergence of a new generation of LatinX artists, including Pulitzer Prize winner Nilo Cruz, Migdalia Cruz, and Marrero herself, among others. In Marrero’s play, Fornés’s character, IF, mirrors many of Fornés’s biographical details: her own Alzheimer’s disease, her lovers, and her plays—some of which she mentions in her conversations with SHE. Meanwhile, SHE mirrors the playwright’s life (Marrero’s). In the conversation with the Undermain cast after the play, Marrero referenced how her mother battled with Alzheimer’s and how MAMI—SHE’s mother—is inspired by her. IF was played by Rosa Mendoza, and SHE by Frida Espinosa Müller. Mendoza’s rendition of IF is particularly inspired, with an undone hair, bodily gestures, and voice inflections that recalls Fornés’s. Müller adeptly embodies SHE—a woman trying to find her own identity in a world dominated by family and by the men in her life. During most of the reading she is seated, and she does not use makeup: her passive body language mirrors SHE’s attitude towards life: living to care for others.

The Undermain Theatre, in Dallas, included a reading of the play as part of their annual “Whither Goest Thou America Festival”. The model that the organization followed during this pandemic season included a subscription series, which gave access to members to a variety of content, including readings such as this one, plays, and conversations with the creators. Instead of offering the live reading of the play, the Undermain created an edited video that mixed a Zoom room with actors reading the play with photographs, video, and other materials to create an affective experience. In their use of different media, in addition to the actor’s reading, is visible the attempt to create a visual language marked by stillness and repetition: images appear more than once, creating a familiar landscape, a dramaturgy of sensation, rather than plot. This strategy dialogues too with Fornés’s plays: characters are defined more by language, repeated leitmotifs, and objects than by the development of the plot.

Cuba emerges as the connection between IF and SHE—their casual encounter at a thrift store, their love for clothes and a sense of style that values what already has a history, justify their relationship—but it is really their shared experience of migration that ties them together. The director, Sorany Gutierrez, and montage editor Danielle Georgiouincluded old footage of Havana’s landmarks in between the scenes—played also backwards. This feature in particular is used with another footage, a short video of a beach—placed in the screen as we hear the characters reminisce of their lives in Cuba. The backward playing is perhaps the best visual effect to represent a generation that—like SHE’s parents, never forgot the Cuba of the fifties, before the Revolution, a time that nostalgia has dressed up as the perfect bliss of the past. A past that is a memory played back and forth, incomplete, almost just a glimpse of what it was, but that also hints to the way in which memories in general are presented in the play by the two characters with Alzheimer: in a playful, but almost static and ephemeral way.

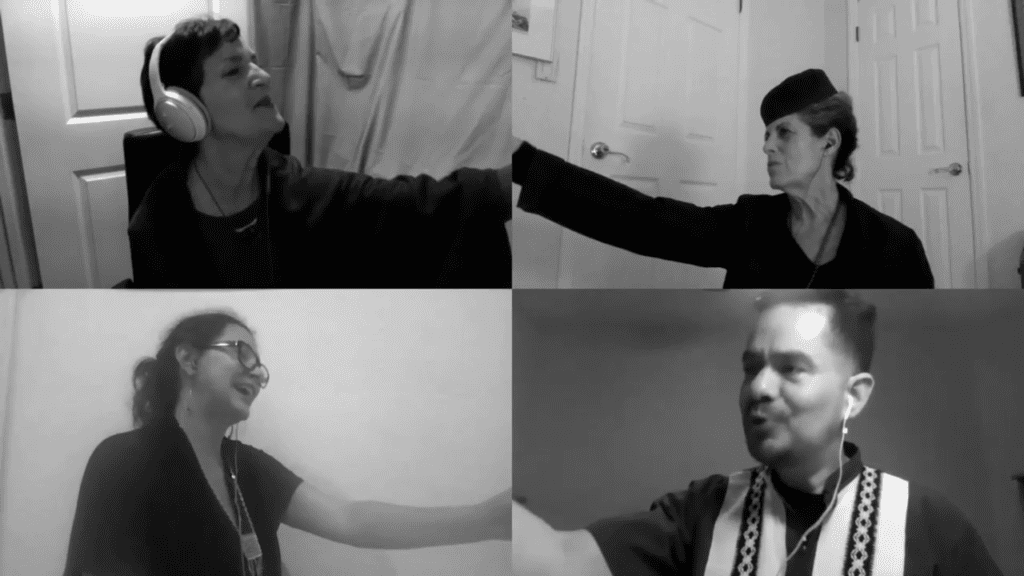

Other actors include Laura Yancy as MAMI, and Armando Monsiváis as MEN (which include six different characters: the Good Ex, Fidel, Jesús, Date, Groom and Papi). The men in the play are articulated in relationship with how the lives of Cuban women are surrounded and often defined in relation with masculine archetypical figures: the father, the ex, the present or next partner, and… Fidel Castro. Castro’s figure—evoked through the performance with a photograph of the leader with his typical green clothes, does not present to the viewers his face—, somehow avoiding a full depiction of the dictator, leaving the spectators to blend in their minds the historical image and Monsiváis rendering. For generations, Cubans on the island grew up listening his hours long discourses, and watching his image in posters and newspapers; for Cubans in exile, he was the person to blame for everything. To both sides, Fidel’s presence was a given, almost a staple of the Cuban experience. In Yancy’s depiction of MAMI is visible the attempt to embody a mother who struggle with her sickness and playfully dialogues with her daughter, sometimes pretending to be a child, sometimes forgetting that she is not one. Yancy’s MAMI is sweet, and vulnerable, although since she is not fluent in Spanish her codeswitching through the dialogue feels forced.

Excerpts of Michelle Memran’s documentary “The Rest I Make Up” (2018) are also used in the play, providing the audience not only with Fornés’s real image, but also with her voice, and her movements. Memran’s documentary was an inspiration, too, for Marrero’s writing, so including it here is both an homage and a hint to the real-life aspect of Marrero’s representation of IF. Marrero dialogues with Memran’s documentary by framing the play as a conversation—similarly to how Memran interviewed and followed Fornés with her camera for over fifteen years. The “Second Hand” of Marrero’s title, then, allude not only to the second-hand stores that IF and SHE visit, but also to the indirect, fictional, and referential nature of her play with Memran’s work. Other editing strategies incorporated to the reading is the use of white and black screens, which invite the audiences to just listen what is being said—or read—by the cast, but at times began to dominate as a mode of storytelling that overwhelmed the reading.

Second Hand Conversations With Irene: Remembering Long Enough incorporates Spanish in many of the dialogues and monologues. The code-switching strategy appears in all characters, and in many instances the actors attempt to speak with a Cuban accent to signal culture. The play takes the Cuban experience in the United States at its core; it is the particular experience of the first wave of exiles after the Cuban Revolution and their relationship with their children who grew up already in the United States. For Marrero, her own relationship with Fornés—a creative non-biological mother figure—is paralleled in the play with her biological mother. Both help SHE, in their own ways, to reclaim her agency and fulfill her own potential. The play calls attention to the relationship between family memories and history. The impact of Fornés and her work for the Cuban American and LatinX theatre communities is well-documented in American theatre, but what about those lives that could have been touched, in a more personal level, by Fornés, on a day-to-day basis, while having coffee someplace near her apartment, or in a thrift store? The play is an exploration of what remains of a person once they are gone, especially if that person is a woman. SHE never had kids—something that her mother, and herself, reflect upon often. For Fornés, her plays were her kids. The play privileges creativity over biological reproduction, subverting stereotypes of femininity that, despite many decades of feminism, are very well alive within the Cuban and Cuban American communities. To that end, IF playfully engages with SHE, teaching her to see objects not only for what they are but for what they could be in our imagination. It is ultimately this call to create alternative realities, or endings for that matter, that brings the characters together. The ending for MAMI is death, as it was for Fornés, and for all of us, but theatre offers the alternative of reimagining what could have been or what we would like to happen, rather than the factual resolution of our everyday experiences.

One thought on “Second Hand Conversations With Irene: Remembering Long Enough”

I am beyond grateful for this thoughtful and provocative review, Lilianne Lugo Herrera. Thank you.

Lillianne’s assesment of use of media hits the spot… «is visible the attempt to create a visual language marked by stillness and repetition: images appear more than once, creating a familiar landscape, a dramaturgy of sensation, rather than plot. This strategy dialogues too with Fornés’s plays: characters are defined more by language, repeated leitmotifs, and objects than by the development of the plot.» And, while I wrote a play and not a virtual script, the artists involved, Sorany Gutierrez (director) and the Undermain Associate Artistic Director Danielle Georgieu captured the improvisational intention of the piece. And yes, the conversation with Michelle Memran’s documentary The Rest I Make Up, is fundamental. Again, thank you to all involved with this much needed platform for the Latinx performing arts.