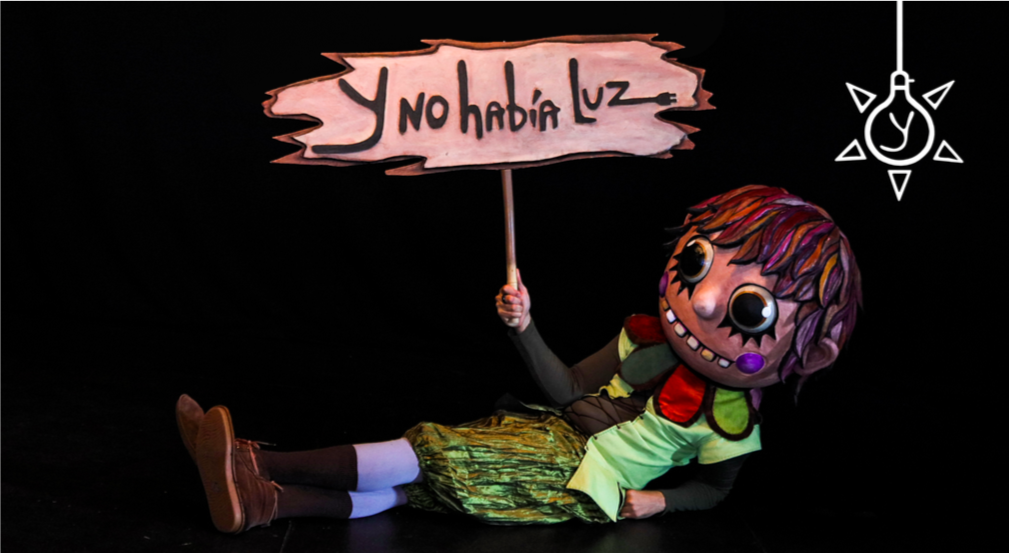

ZEFIRANTE EN CUARENTENA & CRUZANDO EL CHARCO by Y no había luz

By Colleen Rua (University of Florida) / May 10, 2021

While short films have been a consistent part of the work presented by the San Juan, Puerto Rico based theatre collective Y no había luz, the Covid-19 global pandemic centered their filmmaking in 2020 and 2021 as they were unable to host live audiences. The fifteen-minute Zefirante en Cuarentena premiered on Facebook Live on December 15, 2020 and is available on the Y no había luz Facebook page. Cruzando el Charco is a ten-minute film that is part of a larger work and is currently unavailable to view online. A short film about the collective’s creative process in filming Cruzando el Charco premiered at a webinar hosted by the University of Florida on April 19, 2021.

Zefirante en Cuarentena

In a short film celebrating the Y no había luz theatre collective’s 15th anniversary, the audience witnesses Zefirante as he attempts to navigate life in quarantine. The elf-like titular character was first introduced in Y no había luz’s original play which then became a children’s book of the same name, Centinela de Mangó. In these works, Zefirante is mobilized as a symbol of climate justice, carrying seeds of an iconic felled mango tree across the globe on a gust of wind and planting the spirit of Puerto Rico in an act of diasporic healing for those impacted by hurricanes Irma and Maria in September 2017. The character and the book emphasize Y no había luz’s commitment to environmentalism. It is a thread woven throughout their work. In the film, he is half-human and half-puppet, played by Carlos José Torres who dons the oversized head of Zefirante.

We first meet Zefirante to the tune of dreamlike music as he tosses and turns, trying to sleep. He awakens to a day of mundane tasks: washing dishes, sweeping the floor, and scanning the fridge for snacks. Another series of tasks highlight Zefirante’s isolation: putting on a mask, gloves, and spraying his entire body with sanitizer. He tries to find delight in riding a tiny bicycle and tries to find calm in yoga. He is finally inspired by the plants that grow just outside his door. In this moment, Y no había luz does what it does best: transforms trauma into healing by awakening an ecological conscience; an element central to the collective’s mission. As Zefirante interacts with the plants, sniffing, watering, really noticing them, dreamlike slow-motion camerawork kicks in. The moment is suspended in time and is one in which Zefirante is able to transcend his current circumstance by finding gratitude for the bit of nature in front of him. It is as though he and the plants tend to each other. He begins to create, using strips of cardboard and paint.

Gazing longingly through a wall of windows to the world outside, an idea strikes. Zefirante paints an image of Earth on the inside of a trash can lid. Surveying it for its completeness, he lovingly adds a mask onto the face of the planet, protecting it. Zefirante begins to display his work across the windows, asking the world outside: “¿Qué es lo esencial?”. The answers to his question are at once simple and profound, each painted on a sign: “Agua,” “Salud,” “Familia,” “Respirar”, “Amor,” “Bañarse,” “Aprender,” “Sembrar,” “Justicia.” As the camera pulls away from the windows, the building, the sounds of traffic outside, finally resting in the dense trees beyond the city, the viewer is called to action. “Luchar contra todo aquello que contamine la vida.”

Zefirante en Cuarentena highlights viewers’ own isolation while offering the comfort of a space to share with Zefirante. He often breaks the fourth wall, seemingly making eye contact with the viewer, despite the fact that his eyes carry a fixed expression. This ability to connect to the viewer is remarkable and speaks to both the magic of the collective’s collaborative art direction, coupled with Torres’ nimble physicality that work together to create a character, capturing both the whimsy of the spritely elf as well as the longing of being cooped up. In the absence of dialogue, Torres’ movement provides a language of lightheartedness and persistence that serve as a reminder to find laughter in tears.

Cruzando el Charco

In Cruzando el Charco, Y no había luz explores absence. It is felt immediately in the distance created by the screen between performers and viewers. While the piece reckons with uncertainty, fear of the unknown, and loss, it is led by an overwhelming sense of hope, captured in Julio Morales and Nami Helfeld’s direction, Morales’ art direction, and Pedro Iván Bonilla’s camerawork. Cruzando el Charco is part of a larger provocation, El Circo de la Ausencia which began as a visual art installation comprised of a series of toy theatres, each representing a circus act.

The film, divided into three parts, opens with an undulating ocean of blue and green tulle fabric. Several fish, manipulated by puppeteers, splash to the soothing sound of strings. Above the water, Funámbulo cautiously walks a tightrope that stretches precariously from one side of the frame to the other. He, too, is a puppet, manipulated by three puppeteers wearing black, with faces covered to bring focus to the isolated figure perched on the rope. One manipulates his feet, another his head, and the third provides his hands; human hands that clutch a small suitcase. Inside the case: a light. Perhaps his dreams, perhaps his memories. Funámbulo’s origin and destination are unclear. Feelings of absence and isolation around migration loom large for Puerto Rico’s continued struggle against colonialism and a four-year pattern of preparation and recovery in the wake of (un)natural disasters.

In part two, Buscando el Balance, Funámbulo demonstrates feats of fearless dexterity as he balances on one foot and dangles from the tightrope, using his hands to pull him across. He performs confidently and proudly, nearly forgetting his predicament, before a wave of insecurity causes him to sit on the rope and hold on. He is both drawn to and wary of a dazzling mermaid who tosses the rope with the slap of its giant tail.

In part three, La Cuerda Frágil, Funámbulo uses his case to defend himself against a hungry alligator. When flames threaten to burn the rope, he opens his case, finding inside a beak attached to an elastic band. He slips the band over his head, beginning his transformation just in time for the rope to snap. As the camera pulls away, we see that not only does he have a beak, but also a set of colorful wings. He is tired, and as he gets used to his new appendages, he moves in zigzag and circular patterns. Eventually, he finds his direction and flies slowly but surely toward his future.

Evidence of Y no había luz’s collaborative process is strong in Cruzando el Charco. It is clear that their fifteen years of work together has resulted in an ability to communicate without words, to move fluidly as one, and to imbue objects with the spirit of their social justice focused mission. Their sense of humor and delight in a bit of mischief are hallmarks of their creations and can be found in moments where Funámbulo encounters potential predators or when he shows off his circus skills.

Zefirante en Cuarentena and Cruzando el Charco open transformative spaces of healing through an aesthetic of defiant joy in which “joy is not found in the absence of pain and suffering. It exists through it” (Perry). Zefirante and Funámbulo are both confined in different ways, but through joyful movement, actions, colors, and humor, they expand geographic and ideological spaces. For Y no había luz, artmaking in the face of disaster is not only about survival but celebration, and a transformation of the very forces that attempt to stamp out or devalue joy. Essential to their mission is their commitment to environmentalism and to raising awareness of the need to care for the planet. This thread appears throughout their work, most explicitly in Centinela de Mangó, which brings awareness to the role climate change played in the formation of Hurricane María. By revisiting Zefirante in quarantine, an audience familiar with the collective’s work is reminded of his role in carrying out an environmental mission. Multiple iterations of these characters activate afterlives for each story to give audiences access to reenact, reshape and re-remember events. For example, in an educational outreach program for children, participants became zefirantes. By embodying the character, participants were empowered to add their own voices to stories of healing. The evolution of Cruzando el Charco from visual art installation to live performance emphasizes the movement of migration and through Funámbulo’s power of flight, transcends the idea of borders and of migration as a linear pattern. In these afterlives, Y no había luz prompts action, ignites possibility, and joyfully celebrates the spirit of community. As the collective notes in their introduction to Zefirante en Cuarentena, “We are caged, but we are not sleeping because each day we wake up a little bit more.” (Helfeld).

Works Cited

Perry, Imani. “Racism Is Terrible. Blackness Is Not.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 15 June 2020, www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/06/racism-terrible-blackness-not/613039/. Accessed 5 May 2021.

Helfeld, Yari. “Re: Cruzando el Charco.” Received by Colleen Rua, 7 May 2021. Email.