Castelvines y Monteses by Lope de Vega

By David J. Amelang (Universidad Autónoma de Madrid) / 24 July 2021

On April 17th 2021, as the spectators in the Teatro de la Comedia in downtown Madrid were bustling to find their way to their seats, a young woman wearing a baseball cap, jeans and a hoodie walked onstage. She stood there, looking intently at the backdrop wall, impervious to the auditorium of curious onlookers that was slowly filling up behind her. She was soon joined by a man with a straw hat and a woman carrying a mandolin. And another man with a long dark cloak and a guitar case. Then a woman slinging an accordion over her shoulder. Finally, yet another man with a cymbal. All gazing at the wall in front of them, waiting increasingly restlessly for something to happen. Suddenly, at 7PM sharp, the wall split open to reveal a drum set, keyboards, stools and amplifiers, allowing what one suddenly understood to be a musical band finally getting ready for its gig. The lights dimmed around the audience as a hearty “Buona sera, e benvenuti a Verona!” blasted over the speakers, kicking off what promised to be an memorable night: after all, we were not in Verona, but in the heart of the Spanish capital.

It came almost a year later than initially planned, a year full of trials and tribulations for Spain’s thespian community, but finally the Compañía Nacional de Teatro Clásico’s production of Castelvines y Monteses, written by Lope de Vega and directed by Sergio Peris-Mencheta (Barco Pirata), was underway where it was supposed to be. Lope’s dramatisation of Matteo Bandello’s tale of the star-crossed lovers from Verona is considerably less well-known than its English counterpart, Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. And yet it is precisely this involuntary connection – Lope wrote his version of Bandello’s novella completely unaware that Shakespeare had done the same roughly a decade earlier – that set the tone for an exciting and frenetic production that did not ignore the elephant in the room: Lope’s play could never be truly alone in the audience’s headspace, not even in Spain, not with Shakespeare’s to compete with.

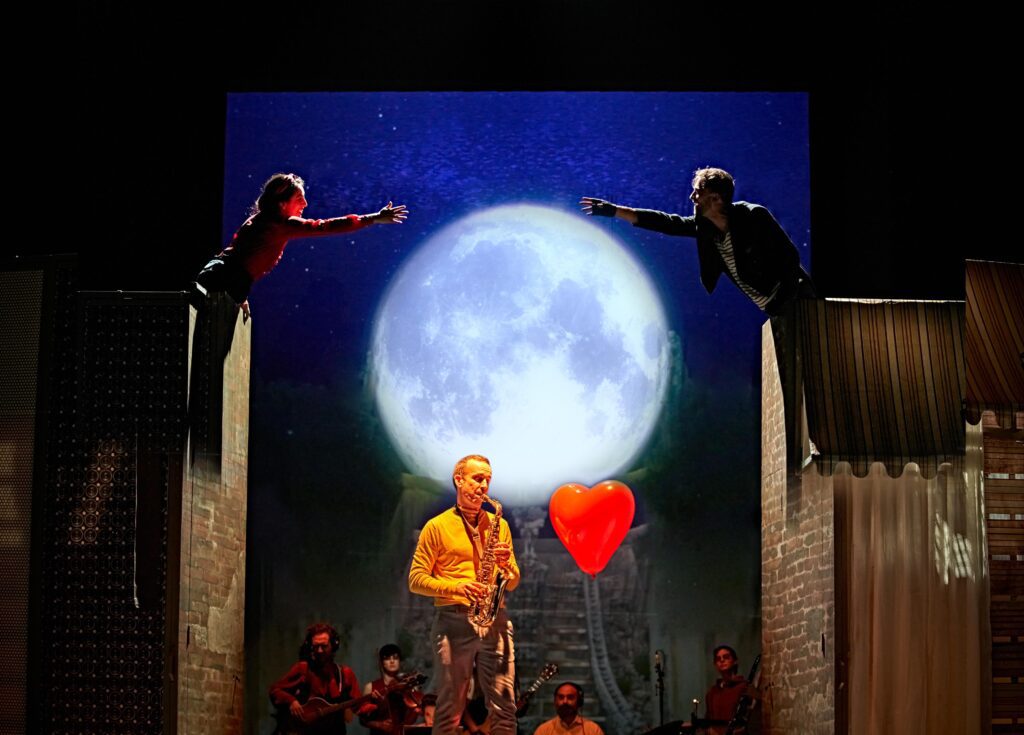

Set in a post-war Verona that brought together the aesthetics of the Italian café-trattoria and the rockabilly culture of the 1950s, Peris-Mencheta’s production can only be described as a joyous – even raucous – spectacle in which there was always a lot happening at all times. For starters, Lope’s comedia merely served as the base layer of the performance, which incorporated passages from other literary works, most notably Romeo and Juliet itself (in Spanish translation), as well as several metatheatrical interludes and games in which the audience delightedly played and sang along. But it was the music that most stood out: over and over again, the characters broke into song, Italian songs from the 1950s and 60s to be more specific. Renato Carosone’s “Piccolissima Serenata”, Mina’s “Tintarella di Luna”, Domenico Modugno’s “Volare”… The whole thirteen-strong cast took turns singing, dancing, and playing an endless repertory of cheerful Pop songs in their original Italian, turning Lope’s Spanish play into a boisterous multilingual musical that was no longer Lope’s. Add to this that the play begins with a costume party organised by the Castelvines family (which the Monteses crash, resulting in the meeting of Roselo and Julia), and the result is that you end up pinching yourself simply to make sure that the astronaut and Little Red Riding Hood dancing swing in front of you are real.

A large contributor to the sense of dizzying extravagance was the set design itself, which was in constant motion. It consisted of a rotating platform, two double-sided screens and a back wall that parted into two, revealing where the band was seated. Not only could the screens be rotated, each side hosting a different part of Verona (a café, a nightclub, a back-alley, etc.), but many of the actors often had to rope-climb them with help of hooks and harnesses to the visible worry of many spectators. This is, for instance, how the famous balcony was staged, with Roselo – and his servant – scaling the wall of Julia’s house in search of his new love – and her maid. From an artistic point of view, this scene was unquestionably the climactic point of the show, as the two pairs of lovers performed a fantastic rendition a quattro voce of Domenico Modugno’s “Musetto (La Più Bella Sei Tu)”, a scene of surprisingly effective intimacy considering that the rest of the cast was onstage behind them playing the song.

The performance carried on in this playful and cheerfully irreverent way up until the two-hour mark, when suddenly things grounded to a sudden halt. The platform stopped spinning, the screens stopped rotating, the cast stopped singing and dancing. Almudena Salort, who played the part of Dorotea, took the stage to explain that this point – perhaps ten minutes shy of the play’s end – was when which they had to stop rehearsals the previous year due to the COVID-19 pandemic. That this was as far as they had gone before it all had to be shut down, and that this was where they left it. Those words hit hard in an auditorium dotted with masked faces and seats left empty as part of the measures in place at the time, as Madrid was slowly making its way out of a third wave of infection cases. While they had not been able to block the performance in its entirety, they finished the play by reciting what was left, and took a bow as they received a well-deserved standing ovation.